If you’ve heard of simulation theory – the idea that our entire universe could run in an extra-dimensional computer – there’s a good chance you learned about it from a high-profile believer like Elon Musk. But how would the average person, someone whose influence does not depend on provocative philosophizing in the dormitory, accept this? How would the idea that the world is not “real” define the way you interact with other people? If you’re even a little intrigued by exploring the subculture, you’ll appreciate A Glitch in the Matrix, Rodney Ascher’s latest documentary on uniquely obsessive personalities.

And if you are wondering, no, the film does not reveal any secrets of simulation theory. Even Ascher tells us that he has no idea whether it is true or not. Instead, he cares less about the theory itself and more about why people believe in it. His award-winning documentary Room 237 from 2012 was about the wild fan theories surrounding Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining. Its successor, The Nightmare, examined sleep paralysis and the way it often constructs terrifying scenarios from the air. It’s easy to draw a line between these films and people who distrust the stuff of reality.

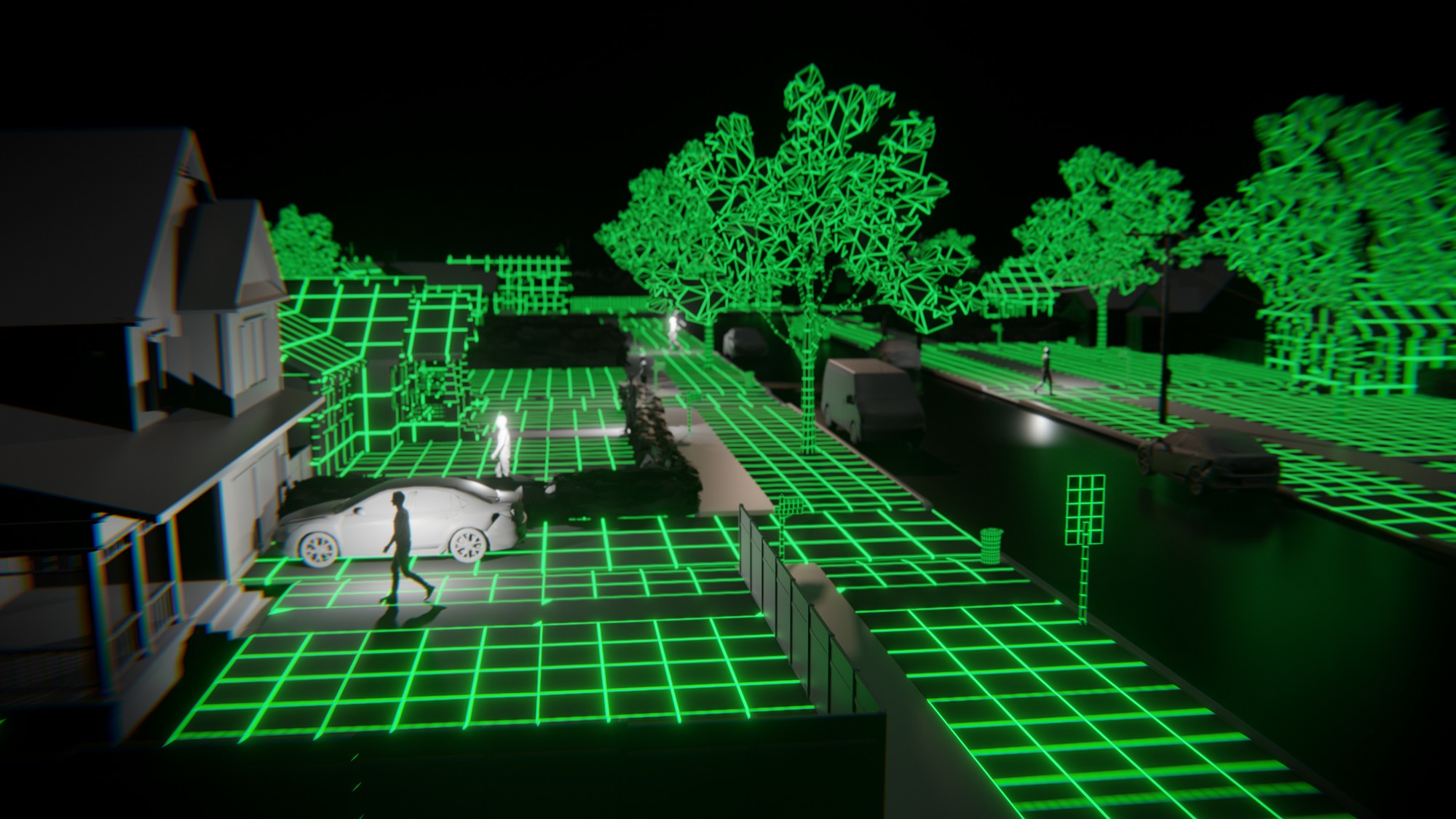

If the title wasn’t enough characters, A Glitch in the Matrix feels like an introduction to simulation theory, rather than a strict discussion. After all, in 1999, the Matrix introduced the concept of simulated reality to an entire generation of emo teenagers (including myself). What it lacks in depth, however, it makes up for in mere observability.

Magnolia pictures

It’s both funny and a bit sad to hear seemingly serious adults – portrayed as cartoonish CG avatars – reject the idea that there are 7 billion individual consciousnesses on earth. Why? Obviously because our universe simulator definitely doesn’t have enough processing power to handle it. The more logical explanation, of course, is that the machine only recycles a few hundred thousand personalities, just as an Assassin’s Creed game generates its large amount by reusing AI code.

Too often I wish Ascher would push his subjects just a little more to test the limits of their beliefs. But I suppose it’s like trying to discuss the shape of the planet with a flat earthher. One subject managed to leave the site of a drunk car accident in Mexico without serious injury or was arrested. He thought it was the simulation that just worked out a successful narrative for him, and not stupid luck and his American privilege in action. How can we convince him otherwise after surviving something like this? One person’s miracle is another person’s optimal simulation path.

If stories like this make you roll your eyes, A Glitch in the Matrix has more meaty material from Nick Bostrom, the Oxford professor of philosophy whose 2003 work sparked modern interest in simulation theory. He suggested that given the tremendous computing power we expect in the future, it is possible that later humans could run simulations of people who are similar to their ancestors. These artificial humans would likely be conscious. And given this possibility, there is a high probability that we are one of those simulated realities rather than the “main beings”. (Alternatively, we could either be extinct before we could develop our own simulation technology, or we could abandon the technology entirely.)

Bostrom doesn’t have many answers in the documentary, but it does remind us that people have been thinking about higher levels of reality for thousands of years. Plato’s Allegory of the Cave was an argument for education and research in the face of ignorance, but today it also describes the way many people think about simulation theory.

A flaw in the Matrix also really surprised me with footage of Philip K. Dick explaining his own beliefs about higher consciousness. As is known, he began to experience religious visions after an operation, about which he finally wrote in his Exegesis, a collection of more than 8,000 pages of notes. Dick sounds like someone who’s caught a glimpse of the world outside of our potential simulation, although the simplest explanation is that he has had severe mental illness his entire life.

While I have some concerns about what A Glitch in the Matrix is focusing on, it’s still a well-made documentary filled with fascinating imagery. Ascher has perfected his ability to visually convey a narrative about his recent films so that you will never be bored. And for people who haven’t heard of simulation theory, I’d bet it would blow them away, just like the people who dare to get out of Plato’s cave.