[MUSIC PLAYING]

ezra klein

I’m Ezra Klein, and this is the Ezra Klein Show.

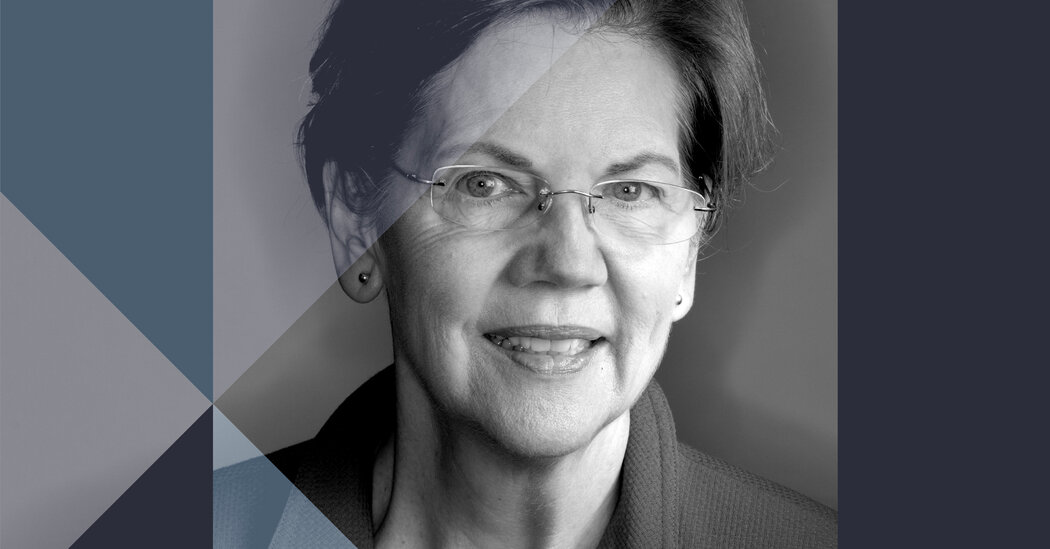

Let me just start the show today with a claim that is going to sound bold, but I think is obvious. Elizabeth Warren is the single most important policy thinker and doer of this generation. If you go back decades now, the research she did and then the way she promoted it and sold it and then got it passed has completely changed how we both view and make policy, particularly economic policy. So “The Two-Income Trap,” which is a book she published in 2004 back when she was an academic, it tilted the axis of the Washington economic debate. It moved the focus from this pretty narrow lens of wages and overall economic growth that had dominated in the Clinton era towards this deeper analysis that we now take for granted on the affordability and precarity of a modern middle class life. A lot of the modern economic debate is built on that. Of course, that research was built on her work on bankruptcy, but it also fed into her work on financial regulation. She proposed this entire new way of thinking about and then structuring consumer protection. And then she made this move that policy wonks almost never make. She got those ideas passed into law. It went from an article in the journal Democracy to a new federal agency that she set up and ran, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. It’s just wild. And then when the Senate Republicans wouldn’t confirm her to run it permanently, she ran for and won a Senate seat in Massachusetts. She became then a member of the Democratic Senate leadership team and a presidential candidate. The closest analog to this in recent American politics is — I don’t know — maybe Pat Moynihan from New York. But it’s a pretty unique career. And it’s by no means over. So in recent years, Warren has led in pushing antitrust back into the conversation. The bipartisan debate we have now over breaking up big tech firms, that’s a debate she really drove with her proposal to do that a couple of years ago. The debate over canceling student debt, that’s a debate she drove with her proposal to do this a couple of years ago. And now Majority Leader Chuck Schumer is signed onto her plan to have Biden use executive authority to cancel $50,000 in student debt. And then this is more subtle, but it’s really important. Warren pays much more attention to staffing than most figures in Washington. And so, she has brought a lot of really talented people up to her staff, trained them herself, and then put them elsewhere into government. There are sort of Warrrenites all through the federal government now, and also in elected office: Katie Porter in the House, the member of Congress from Orange County, California, who’s become a total star. That’s a former Warren student. So I could keep going on. But the point is simply this: a lesson of the past 20 years is that what Elizabeth Warren is thinking about now is what Washington is going to be talking about next. And that’s the lens with which I read Warren’s new book, “Persist.” “Persist” is built around these identities Warren holds, or that she has held— mother and teacher and planner and fighter and learner and woman. But each of those identities is then used to make a series of arguments for the policies that we should pass. And a few of them, in particular, caught my eye. One is Warren’s effort to develop here a truly pro-family progressivism to put children and childcare at the center of the progressive agenda. And another is to change the lens through which we look at the economy, and particularly, the lens through which we look at inequality and distribution, by moving it from a focus on income to a focus on wealth. So in this conversation, I wanted to draw those ideas by drawing on another of Warren’s identities, which is policy wonk. This is just a much weedsier conversation than most politicians will have or can have. And for that reason, I think it is really worth the time. As always, my email is [email protected]. Here’s Senator Elizabeth Warren.

So let me begin here. Childcare costs have skyrocketed in recent decades — they have risen much, much, much, much, much faster than median wages. I think the figure you have in the book is that when you became a new mother to when you became a new senator, they rose by 900 percent.

elizabeth warren

Mm-hmm, inflation adjusted.

ezra klein

Inflation adjusted. In a bunch of states, it cost more to send your kids to childcare than to in-state tuition at the university. Why have they gone up so fast?

elizabeth warren

Well, they’ve gone up so fast because of basic economics — supply and demand, partly. There are more and more parents in the workforce — mamas, in particular, who have gone to work. And childcare centers run on incredibly thin profit margins. In fact, think about it this way. Look at all they have to do to be able to take care of little babies or toddlers. They need lots of teachers. They need specialized space. They need lots of certification. They need to make sure they’ve got appropriate fire escapes and that they’ve got carrots all cut up and ways to help children get to the potty. And they’ve got all of those expenses. And yet, they can’t charge what that costs, plus a nice, fat margin, because parents can’t afford to pay for it. So childcare is one of these things where there’s a lot of demand, a lot of people who need childcare. And that was true before the pandemic. Now with the pandemic, it’s just really intensified. And yet, the squeeze, again, before the pandemic on childcare workers at childcare centers was huge. They kept wages rock bottom, which meant high turnover. And now with the pandemic, estimates are that as many as half of all childcare centers closed during this pandemic. So what was already a crisis became a mega crisis.

ezra klein

So is there a way to make childcare cheaper? Or is the right way to think about it that we simply have to spend more on something that is socially important enough to spend more on so the wages are good and the centers are high quality?

elizabeth warren

Yeah, the right way to think about it is that we need to spend what it takes to take care of our children. And this is an investment in our children’s future. We call it childcare. It’s childcare and early learning. Keep in mind, even stay-at-home parents, if they have the resources, will often put very young children into three days a week morning playgroup, whatever they call it. But the point is, where children can be with other children, where children can be with other adults, where they can develop a bigger vocabulary and learn things, like no biting, how to stand in line, things that are important to get them ready for learning experiences in school. We don’t ask parents of third graders to come up with the full ticket for what it takes to educate a third grader. We shouldn’t be doing that for parents of 4-year-olds or 3-year-olds or 2-year-olds or even our littlest babies.

ezra klein

So Joe Biden’s American Families Plan, it is $200 billion to establish free universal preschool. It’s got $225 billion to fully cover childcare costs for lower income families. It caps those costs then at 7 percent of income, up to about 1.5 times the state median income. What do you think of these ideas? There are some similarities here to what you’ve proposed, some differences. How do you look at what he’s come up with?

elizabeth warren

It’s a good start. We need more. I’ve done the numbers, talked to a lot of folks. And we think basically to provide universal childcare that is available, high quality, affordable childcare for every baby in this country and for every mama and daddy in this country, and to raise the wages of every childcare worker and preschool teacher, it’s going to take about $700 billion over 10 years. But the advantage to it is something that we will reap the benefits for generations and generations to come. Increased productivity — mamas and daddies who can go back to work. Better wages — we talk about a jobs plan as infrastructure. Then we raise the wages of the predominantly women who are working in childcare and early childhood education. And best of all, we get our babies off to a good start.

ezra klein

So if I go back to “The Two-Income Trap,” one of your earlier books, you were very worried in that book about universal preschool creating a preference to send children to preschool as opposed to being a stay-at-home parent, so there you had an idea for a subsidy to stay-at-home parents, too. Has your thinking changed on that?

elizabeth warren

What we were talking about in “The Two-Income Trap” is how having both parents in the workforce was not giving families the kind of boost that they thought it was, that, in effect, what a generation earlier — the kind of life that one income would buy — took two parents by the time of, say, around 2000, 2005, along in there, when we wrote this book. My view has really expanded on both the educational part of childcare. We need to make it available for all of our babies because it’s good for our babies and their development, but also the infrastructure part of it. We want to increase productivity in America, we need to put our money directly into building enough childcare, the same way we put our money into roads and bridges. Interestingly, we’ve already taken step one on helping all parents. And that is, right now, we’ve got this child tax credit that goes, largely, to the majority of parents in America. That’s a good step one. And that’s going to buy a lot of new clothes and make sure there’s nutritious food on the table and help, in some cases, with rent. But we need to be able to make it easy for parents to go to work. We need to give those experiences to our children. And we need to raise the quality so that good childcare centers are out there and available for everyone. And we can do that. We just need to make the investment.

ezra klein

So some of your colleagues on the right, they feel that universal childcare is elitist. JD Vance, who looks like he’s running for Senate in Ohio, he described it as a class war on normal people. Because most people — they’re a plurality — if you poll them, they support a single breadwinner model in their families. Is there something to the critique, or how do you answer the critique that rather than being pro-family, this is pro a certain type of family? That there shouldn’t be such a preference. We shouldn’t be spending $700 billion to make it easy to go to work if we’re not spending the same amount of money to make it easy to stay at home and take care of a child.

elizabeth warren

This is pro-family. It’s pro-family. It’s pro-child. It’s pro-women. Because can we all just be blunt about this? I know there are daddies out there who are primary childcare givers. But the burden of childcare falls disproportionately on women. I talk about this in my book — this latest book, in “Persist” — about both what happened to me and how I nearly got knocked off the track, almost quit my first real teaching job, and then I update it through the stories of the pandemic. Look at what’s happened, the number of women in this nation who have said, I’m not even going back. I’m not even going to try. It’s just too darn hard. There are many families that need that parent’s paycheck, whether that’s a single mom, a single dad, or a mom and a dad or two moms or two dads, who are working and bringing in those paychecks. And the idea that we don’t want to help those families? No, these are our babies. This is our future. And this is our productivity right now. Infrastructure — we invest in roads and bridges so people can get to work. We invest in communications so people can work. We need to invest in childcare so people can work.

ezra klein

But I think the question is, should it pay to be a stay-at-home parent? Is there some way that public policy should be constructed such that you are able to equalize that and you actually give people who stay at home just quite a bit of money?

elizabeth warren

It’s interesting you would raise this. I talk about this in the last chapter of the book on people staying at home. If that’s what they want to do and that’s how they can make the money work, good for them. If people want to go into the workforce, good for them. For many people, they don’t have a choice. They have to go into the workforce. And this is why we build a childcare infrastructure. But I’m going to pick up on your other point. I talk in that last chapter about how women take off time for caregiving, sometimes for children, sometimes for elderly parents, and what those years of zero income do to their long-term retirement prospects. So one of the proposals I’m advancing in the book and in real life is that we change Social Security so people who are at home, caregiving, get some credit for those years. And they’re not both giving up money while they’re not working, but also giving up money when they turn 65 or 72, and they must retire. So, sure, there are adjustments we ought to be talking about because of the different ways that people live. But most of all, we should be starting with our values: taking care of our kids, giving their parents an opportunity to work and making those jobs high quality jobs, well-paying jobs for all the people who are in the caring professions.

ezra klein

You have a remarkable statistic on this in the book, which is that if our labor force participation rate for women had grown at the rate of Norway, if we matched Norway now, our economy would be $1.6 trillion bigger. And if you look back at that, labor force participation for women went up in the ‘70s, went up in the ‘80s, went up in the ‘90s. And then right around ‘99, it stalls out in America, but not in our peer countries. Why do you think that was?

elizabeth warren

So, actually, I think that’s the heart of it. And remember — you’re leaving out one part to it — in all those earlier decades, as women are returning to work — or going into the workforce — and it’s principally moms with babies. Women who didn’t have children were already in the workforce. So the big differential starting in the ‘70s is that women with small children are starting to go back into the workforce. And it drives up GDP in America. So my argument around this is to say, when you look at these data, that when it flattens out and mothers just top out around 2000, saying, “I’m just not doing this anymore,” I think the reason is, it’s just too damn hard. It’s just too damn hard for many, many people. And childcare is right at the heart of that. I tell the story in the book about how I got fired because I was pregnant from my first teaching job teaching special education, I’m at home with a baby. And I decide I’m going to go back to school. For me, it’s this crazy idea that I’m going to go to law school. And I make a list. You know me. I make a plan of all the things I got to do to get ready to go to law school, like figure out how I’m going to pay tuition. I was very lucky there was a state school nearby. And I could do it for, I think it was around $450 a semester, and so on. So I’ve got this all worked out. I’m down to what car, right? I persuade my first husband to trade in the beloved Mustang and get a VW Bug because it’s going to be cheaper to drive. So I am planning this out. I got this thing knocked in the head. I am ready to go finish my education. And what nearly kills me? Childcare. I came within a breath of just not getting childcare for my not quite 2-year-old daughter, which would have meant I couldn’t have gone to law school. I mean, there’s no “leave her in the lobby while you’re at school and try to finish.” So I say this by way of saying it was so hard back then. And it was hard when my daughter had her babies. And if we don’t make change, it’s going to be just as hard when my granddaughter looks for childcare if she has babies. And that’s wrong. Childcare needs to be available. It’s not. It needs to be affordable. It’s not. And it needs to have people working in the field who see it as a career because it pays well enough for them to be able to stay in the field.

ezra klein

I found that story very — both of the versions of that story very moving in the book, and also the fact that you were able to potty train your daughter in five days to be —

elizabeth warren

Oh. [LAUGHS]

ezra klein

— as somebody with a toddler, one of the singularly most impressive stories I’ve ever heard in my life.

elizabeth warren

I just want to point out on this, I will tell no secrets, but I want you to know, Ezra, I am here today courtesy of three bags of M&M’s. I will say no more.

ezra klein

Bribery can be effective as a parent. You think you’re not going to do it, and then you do.

elizabeth warren

Yeah.

ezra klein

I want to ask you about the flip of it, though. You’re talking about how hard it is to go back to work with a child and what we can do to make that easier. There’s another thing, and this is something you actually predicted in “The Two-Income Trap,” that as the economics of this got harder, people would often not have children they wanted to have. And we know a lot of young families report not having the children they wish they had. So beyond what we’ve talked about here in terms of childcare and universal pre-K, what can we do to make it easier for parents to have the families they want?

elizabeth warren

Well, I do. I think the heart of this one is childcare. I think making it clear that if women leave the workforce, that we’re going to have some protection for them. That’s paid family leave if it’s short-term. If it’s a longer term than that, I’m talking about Social Security. But this problem you raise is serious, Ezra. I was in Japan and China a couple of years ago, visiting as part of my Senate obligations. And I’m a senator on Services Committee — and also in Korea. And I had off the books meetings at night with young women, young dads, who just talked about how, if it gets hard, you don’t have kids. And when you don’t have kids — I was talking with demographers about how worried they are about what that means long-term for a country. People are living longer than ever. And if we don’t have young people coming in, coming into the workforce, and having babies, we’re not going to be able to sustain a robust economy going forward and to be able to take care of seniors. So, this is serious business. To me, this is what policy is all about. You have to think about these pieces, put them together, and say, let’s make changes now at the federal level that we can make, that we should make and that will make a difference for this country and put us on a track, both for more opportunity for individuals, but also, collectively, a stronger, more productive economy.

ezra klein

One of the pieces of this that I think people often don’t count as family policy, but very much is and is in your plans, is housing. So can you talk a bit about pro-family housing policy?

elizabeth warren

Yes, so as you know, Ezra, I have a plan for that.

ezra klein

No kidding.

elizabeth warren

Yes. So let’s just start out really quick with the importance of housing. The data just show us over and over and over that safe, secure, affordable housing means that people have better health, and their children do better in school and stay in school longer. So you want to make an investment in families, make an investment in housing. What’s the problem in housing right now? Well, it’s a supply and demand problem. And the reason is because demand has gone up. Population has increased, but supply has not. And there are multiple factors on this. First one is just on the private side. I grew up in a two-bedroom, one-bath garage converted to hold my three brothers. That was the house we grew up in. Private developers with a little help from the government were building those after World War II, lots and lots of them. They’re not building those anymore. Today, a lot of the private development has gone to the McMansion or the high dollar condo. And the reason is just — I’m not mad at anybody. It’s just they have better profit margins. So that’s where development has gone. At the same time, the federal government, which also used to put a lot of money into developing new housing units for moderate income people, for the poor, the Faircloth Amendment gets passed in the late 1990s that basically puts a cap on all federally financed housing. So it says, if the federal government adds one new housing unit to the existing stock, it has to remove a federal housing unit. So our population goes up for the last 20 years. And the answer has been supply has not gone up. So the reason I identify this, to start with, it means it’s a problem you’re not just going to solve with housing vouchers. I get it. Vouchers can be important in some circumstances. But we need supply. So I put together a plan. It costs about $500 billion roughly. And it would produce more than 3 million housing units. Estimates are — Moody’s says that would reduce overall rent in America by about 10 percent. And if we do this right, you can do it in lots of ways. So some of it is directly. Let’s just build some of this stuff. Some of it is partnering up with private industry to build it. Some of it is saying to communities, the federal government will put in money, if you will agree to change the laws to make housing construction cheaper and density easier in your area. Federal government could put up the money for the elementary school that will be needed if more people are living here, or the exit ramp off the freeway. But the idea is, let’s make the investment from the federal level for housing for our people. Because when we do that, we create more opportunity for everyone: good jobs in the short run. By the way, the housing plan produces over a million jobs, good jobs, in the short run. And in the long run, stable, healthy families.

ezra klein

I want to go back on that relationship between the federal government and states and cities for a minute because one of the supply and demand dimensions is that over the past 30, 40 years, economic growth got way more concentrated in different places. But some of those places, like the one where I live — San Francisco — have made it almost impossible to build housing. So the statistic people like here is San Francisco has more dogs than children. And for a city that thinks of itself as progressive, that is an unbelievable embarrassment. So talk a bit about what is the federal government’s role in unwinding some of the supply constraints in cities where there is, I think, an economic and, for progressives, an ideological interest in making it affordable for families to live there so they can earn high wages and be part of those industries.

elizabeth warren

You know, I see what you’re talking about just from a slightly different angle, and let me describe it this way. The housing shortage in America, I know you see it up close and personal in San Francisco. You see it in Boston. You see it in these vibrant cities. But you know where else we see it? You see it in mid-sized cities across America. You see it in rural America. A lot of our housing stock has declined. It’s fallen apart. Housing doesn’t last forever. And the consequence is, look how the pieces fit together. You either go to San Francisco, and you can’t afford housing. Or you go to some small town in the Midwest, and you can’t get housing. It’s just not there. There’s just no availability. And then you combine it with no childcare in either place that is affordable, available. When you start hitting people with a one-two punch — and then let me just throw on top of that, for young people, you’re trying to manage $40,000 of student loan debt, $50,000 of student loan debt. What we’ve done to young families — because I think this is partly a generational issue, and I talk about this in “Persist” — we’ve created this circumstance where young families just can’t get going. And actually, that’s what the data are showing, that young families are putting off having children, putting off marrying, putting off buying homes. And here’s the one. If all of that and you’re saying, well, but I’m not a young family, I don’t care, putting off starting businesses of their own, putting off starting that small business, the startups that are the vibrancy of our economy. We miss all of that when we don’t make these core investments. So, here’s how I think of this moment in America where, in the last year, we’ve lived through a global pandemic, a racial reckoning, an armed insurrection. We have a new president. And we have just passed an historic rescue package. So now we have our toes on the starting line for big structural change. The door that is so often slammed tight and locked for big change is open. Now, not wide open, but it’s open an inch or two. And this is the moment where we can make not just a nibble over here or a tweak over there. But we can make the kind of robust investments that will open up opportunities in San Francisco and in Utah and in Illinois and in Oklahoma and Kansas and in Massachusetts. Open up opportunities all across this country. “Persist,” it’s not about the past. It’s about pulling all of those data and the arguments and the stories, the very personal stories, to say, “This is what we need to do in the next 100 days. This is what we need to do now, and we can.” [MUSIC PLAYING]

ezra klein

I want to go in on the student debt for a minute because there are a bunch of topics here where, very quickly, we’re going to end up talking about the filibuster. And people all know what we think about the filibuster. Student debt isn’t one of those. There is a possibility — I think it’s quite plausible — of canceling $50,000 in student debt through executive authority. Majority Leader Chuck Schumer is with you on this now. That’s a big deal. He was on this show a week or two ago, arguing for it. And the Biden administration has been more resistant here. And let me try to frame the argument I hear about why not to do it, which — I’m going to pull these numbers from Adam Looney at Brookings — that if you cancel $50,000 in student debt, the bottom 60 percent of the income distribution only gets 34 percent of that benefit. So it’s not a sufficiently progressive enough way to spend that money. What’s your response to that?

elizabeth warren

So I look at the same numbers he does. And there are some others he doesn’t talk about. And there are a couple I want to mention. The first one is 40 percent of the people who are carrying student loan debt right now didn’t get a college diploma. So they are trying to manage student loan debt on a salary that a high school grad gets. And it is bone-crushing. Sure, there are people who can look at $12,000 of student loan debt and say, oh, that’s not such a big deal. It’s a big deal if you’re making $32,000 a year. And then the second is to look at the Black-white wealth gap around this, which is enormous. Let’s start with African-American students: more likely to borrow money to go to college, borrow more money while they’re in college, and have a harder time paying it off when they get out of college. I’ll give you one stat that’s in “Persist.” And that is: 20 years after you borrowed money to go to school, the typical white borrower still owes 5 percent of their student loan. The end is in sight. They’re almost there. The typical Black borrower owes 95 percent. They’re going to be paying forever. So the number is deliberately chosen for this. Canceling $50,000 of student loan debt would close the gap among those who have this kind of debt by 25 points for African-Americans and by 27 points for Latinas. So doing this would be transformative for millions of people.

ezra klein

I want to hold the devil’s advocate position here for another second. The counter argument you’ll hear on this is that the benefits you’re talking about — closing the Black-white wealth gap and helping people who did not graduate college, but have this debt — you could get the bulk of that benefit by canceling debt up to 15,000, up to 20,000. That it’s when you go up all the way to $50,000, you begin to get these more — I don’t want to say regressive, but you get these more distributional concerns. So why not just do 10 or 15 or even 20,000 and save the rest of the money?

elizabeth warren

I looked at these numbers to begin with. $50,000 is where you can do the most good by canceling the student loan debt up to that amount.

ezra klein

So let me then flip this because this is actually what changed my mind on this. Matt Bruenig over at the People’s Policy Project had a good look at this, that this when you look at it from wealth and not income, the entire distributional structure here flips. And that yes, some of the people with a lot of debt have high income, but they have very, very low wealth, which gets to what you’re saying about the Black-white wealth gap. And this gets to something that I think is not just in your student debt plan, but also in your tax plans and in your economic philosophy more broadly, which is that you focus on wealth a lot more than other politicians do. Our political system focuses on income pretty rarely wealth, but the wealth picture creates a very different sense of society, and in some cases, different policies. So can you tell me a bit, in student debt, but also otherwise, about how things look different when you look at them through wealth rather than income?

elizabeth warren

Can we talk about through taxes? Because that’s the easiest place to see this. I mean, this just shows up everywhere. Oh, I know. Let’s do a wealth tax. But the reason for that is because — think about it this way. You’ve got a teacher who makes, let’s just say, $50,000 a year and is carrying $100,000 of student loan debt. Think about what her economic circumstances look like overall. And then you’ve got someone who inherited or sold a business and is sitting on top of half a million dollars a year, but only has an income $50,000 a year. The rest is all capital. They keep it all, they don’t sell. As long as they don’t sell, they don’t have to realize any gains. They will pay exactly the same taxes. But look how vastly different their economic circumstances are in terms of how vulnerable they are to any bump in the road, but also what it takes to build going forward, build security. If you’re already sitting on a few million, it’s not that hard to get a few million more, right? You invest and make it happen. But if you’re already in a debt hole, it’s hard. And that’s why with the rise in student loan debt, we are seeing fewer and fewer young people start businesses. Look, I talk to young folks who will say, yeah, I had this great idea, or my roommates from school had this really terrific startup idea. And everybody is willing to live in one apartment, seven of them, and eat ramen noodles. But I couldn’t join because I had to make a student loan debt payment of $620 a month. Just couldn’t do it. Or some who’ve tried it, then find that the $40,000 they borrowed while they were in college is now $100,000, and they are in big trouble. So we need to think more, when we’re trying to be progressive in our tax structure and progressive in our investments in ourselves, in each other. We need to think not just about this year’s income. We need to think about wealth overall.

ezra klein

I want to try out a frame on this to you, which is that if you’re worried about inequality, the most important question is, who benefits and who loses from compounding interests?

elizabeth warren

Oh, that’s interesting.

ezra klein

So the people with a fair amount of wealth, right, you have money in the market, or you have money in other things that have a return. And it just keeps compounding and compounding and compounding. And over 10 years, a bit of growth ends up being a lot of growth, a lot more money. But, as you were talking about with student loan debt and other kinds of debt, if you’re in debt then it’s just your debt that is compounding and compounding and compounding. But your money, your assets, to the extent you have any, don’t. Well, then it goes in the other direction. You just get deeper and deeper and deeper into a hole. And very little of public policy is about who gets to benefit from compound interest. But if you care about inequality over time, you care about assets over time, everything is about who gets to and who doesn’t get the benefit, and who’s harmed by compound interest.

elizabeth warren

Oh, Ezra, you’re so right on this. Just the other day, a story from a young woman who was explaining that she’d gone to college, she’d been very nervous about borrowing money, but she carefully thought she had an amount that was OK, wasn’t quite sure, graduates, doesn’t get the job she wants, decides that the way she’ll do this is she’ll improve her credentials — she’ll get a master’s degree — puts her loans on hold without quite recognizing compound interest. And all of a sudden, what she thought was a manageable student loan debt is now hitting six figures. And she’s looking at it, this thing, saying, I don’t know how in a zillion years I’d ever pay this thing off. This isn’t just a young person’s problem. Right now, there are 100,000 people whose Social Security checks are being garnished. And here’s the thing — the estimate is for a lot of them, when they’re being garnished because of old student loan debts that they still have not paid off or they had guaranteed a student loan for a beloved grandchild or a child who is unable to pay, that much of this garnishment — I saw an estimate the other day — actually won’t even service the interest. So the only way they will get out from underneath these loans is to die. That shouldn’t happen in America. [MUSIC PLAYING]

ezra klein

Are billionaires a policy failure?

elizabeth warren

No, I don’t think so. But I sure think they ought to be paying a fair share. Look, my view on this has always been: you make it big, good for you, you know. And you’re going to tell a story about how you worked hard, and you had this great idea. And it came along at the right moment. And you made a bazillion dollars. Good. But keep in mind that nobody got rich on their own, that the business you built, if you built it here in America, you built it using workers all of us paid to educate. You built it getting your goods to market on roads and bridges all of us helped to build. You built that business protected by police and firefighters that all of us paid their salaries. And that’s fine. We’re glad to do it. That’s what infrastructure investments are all about. We’re glad to do that. But when you make it big, then you got to pitch in so that we can build a stronger education system, build roads and bridges, support our police and our firefighters. And we have to have the resources to make this happen. And that’s where we’re in a bad place right now. So last year, the 99 percent paid about 7.2 percent of their total wealth. That’s what you always want to focus on, of their total wealth, in taxes. The top 1/10 of the 1 percent, they paid less than half as much — 3.2 percent.

Ezra, it’s just not fair. So that’s my 2-cent wealth tax, 3 cents, a little bit more, when you hit a billion in terms of wealth. But think about this, Ezra. A 2-cent wealth tax would produce, over 10 years, $3 trillion. Add in a real corporate profits tax. You tax them on what they report publicly in their audited financials, 7 percent on that. And just about double IRS enforcement aimed all at the top at the billionaires, right, and all of their tax schemes. Those three changes in tax policy will yield about $6 trillion that would pay for everything that President Biden has laid out so far in the infrastructure plan, everything laid out in the caregiving plan, family plan, and leave you with about $2 trillion left over. The idea is, you made it big, good for you. But pitch in 2 cents so everybody else gets a chance to make it in America.

ezra klein

Given what you’ve said about the degree to which we all build atop the public sector, we build atop the knowledge that has come before us — you have a great quote from Jeff Bezos in the book about how much had to happen for him to do what he did, right? He sees that very clearly when he’s talking about it conceptually, but of course, lives in a state without an income tax. To what degree are we responsible for our own success? And what does that imply for tax policy?

elizabeth warren

It’s a seamless intersection. It’s about what you’re born into, but it’s also about what you get out there and do. So if you’re born into a family that has buckets and buckets of wealth, you’re going to have one opportunity after another after another after another after another after another. You don’t have to be very good. You don’t have to work very hard in order to live a life of great security. If you’re born into a family that’s already in a deep debt hole, you’re born into a family where your parents are trying to work two and three and four jobs just to hold it all together, then you got a lot of hard work to do just to make it to the starting line in the Great American Race. And if you thought about America over the next 100 years, what do you want to see? You want to see an America that has a robust economy, a strong democracy? Those are the things that are likely to keep us a nation of great promise. What would you do to create that? And the answer is you’d invest in your people. It’s your best resource, right? And how would you invest in them? You’d invest in them by investing in education. You’d pick them up from the time they’re babies, and you’d say, I want you to get as much education as you can. Not just off at high school, not just have to take on costs or put hurdles in your way, I want you to get educated. And we say, I want you to live in safe housing and secure housing. I want you to get the healthcare that you need. And I want you to grow up in a family that doesn’t just feel crushed by the economic struggle to keep going day to day. And then come of age in an economy that’s vibrant, where lots of small businesses are starting, where competition is real, where it’s not crushed by giants like Amazon and Google, but where there’s really opportunity for everybody to get out there and show what they can do. And I get it. Not everybody will show a lot, but some will. And everybody will have had a chance. To me, creating those opportunities, opening those doors, is what it meant to me to be a teacher and what it means now to me to be a policymaker. I want everybody in this country to push our federal government right now at this moment to make the investments that will make us a stronger country, not just over the next six months, but a stronger country for the rest of this century.

ezra klein

I want to ask also another version of this question on how we value people in the economy. Because people get rich; we value them a lot. And we assume culturally that you did something great to get rich. That’s part of what your point is about complicating that. But there’s also this question where then we also assume that people are worth whatever they make, that somehow the economy is making wise decisions about what different professions are worth. So I want to ask this in the sort of — the Harvard economics and bankruptcy teacher part of your history. Why is a management consultant paid so much more than a teacher? What goes into that economic valuation?

elizabeth warren

We got some real problems in this country. Look, you noticed when we were talking about essential workers, nobody put management consultant in that category. It was folks who actually delivered food, right? Look, to me, this is public school teachers. This is the right place to talk about this. I taught special ed. I think the work that I did was enormously valuable. But nobody is going into teaching special ed for the money. They’re going into it because they believe in the work. And we have become a country that talks about monetizing everything. And I think that this is one of the reasons that we have gotten so badly tangled up on things like tax policy. It’s as if, somehow, the billionaire, the guy who worked hard — I always want to give credit, but come on, also got lucky — had the right idea at the right moment and the right people came along. Jeff Bezos, he not only talks about he never could have started Amazon if America hadn’t invested in a postal system and roads and all that infrastructure that was in place. He also got a $200,000 loan from his folks to get going. That the people, though, when they make it big, it’s as if the rest of us are afraid to ask them to contribute to the kind of core structure that lets that happen in America. You hear this conversation: freedom, I’m for freedom, but freedom doesn’t mean that you let your roads and bridges fall down. Freedom doesn’t mean that you don’t educate your children. We need to be willing to face head- on that we need more revenue to make this country run and to build out opportunity for everyone. It’s about being fair and having a competitive market. That’s a second part to it. We need to enforce our antitrust laws so that everybody gets a chance, not just the big guys, that once they get big, get to stomp out everybody else.

ezra klein

Well, let me use that as a jump to antitrust. You mentioned Amazon and Google and Facebook a minute ago. You have a more skeptical take on the technology industry than I think many have in recent years. Though it’s becoming a more popular take. You also, in the book, you criticized investing in robots as a way to boost productivity. You talk about investing in children instead. But I actually wanted to ask about your positive vision of technology. There are things that are getting built, designed. I actually heard about this in Joe Biden’s 100 days speech on climate and other things that could help solve progressive problems. So how do you think progressives should think about technology? What technologies are you excited about and you want to try to use the state to accelerate? And then what do you think are some of the impediments to that?

elizabeth warren

Climate change is the ultimate. We need research and development. Healthcare. We need research and development. And I’m willing to make public investment in that. We’re going to need to find a way to deal with all the carbon in the air right now. We’re going to need to find more ways to be able to produce responses to pandemics faster, right? So I’m there on that. But what worries me is the giants now stomp out competition. Let me give you the example. So Amazon runs this platform that if you want to be able to sell your goods through the internet rather than standing out on the street corner or having a bricks and mortar store, you pretty much have to go through Amazon. OK, so now you do the platform. But what Amazon does is they scrape off data from every one of those transactions. And then they glance over and say, hmm, that Ezra Klein, he’s gotten some clever things together. And he’s now starting to make big money. We will now go into competition with Ezra. We may name it Amazon, or we may not name it Amazon. But we will put the competitor to Ezra’s product, having climbed up on Ezra’s back for all of the early information and all of the risk taking, and now come in and scrape it off. You do that once, then do it 100 times, then do it 1,000 times, and it begins to stomp out competition in this country. And so, the way I see this is that I believe in markets. But markets need rules, and those rules need to be enforced.

ezra klein

Is this a situation where the ways in which markets trend towards — or have been allowed, let me say it that way — to trend towards the dominance of major players is actually worryingly making people lose faith in markets? I often see you as fighting — it’s not a quiet fight, but I don’t always think people quite realize what you’re doing to sort of restore the idea that markets can be a tool of social progress to progressives who have turned on them because they’ve seen what has happened when they’re deregulated. And so, as I understand what you’re saying here, it’s that if you want to see the kind of technological advancements that markets really could give us, you’re going to have to have government take a much stronger hand and keep those markets from becoming the tools or the playthings that are dominated by just a couple of gigantic producers who have unusual power over them.

elizabeth warren

That’s right. We need to enforce the laws on the books already. The Department of Justice Antitrust Division needs to be on the job. We have got to break up these giants. And in places where the courts have been stacked in a very pro-corporate direction, that’s another whole conversation we could have. But every place where that has happened, if necessary, then Congress can revisit and change the language of the laws to stop the courts from undercutting enforcement of the competition rules. To get the benefit of markets, we need competition. We need a cop on the beat to make sure everybody is following the rules.

ezra klein

There are always in these conversations 100 more questions I would love to ask you, but I know you’re tight on a 9:00 AM out. So let me ask you what is always our final question, which is, what are three books you would recommend to the audience?

elizabeth warren

Oh, so now you know that I’m in audio. I do mine with the earphones.

ezra klein

I didn’t know that.

elizabeth warren

Oh, you didn’t know that?

ezra klein

No.

elizabeth warren

I love listening to books.

ezra klein

What speed do you listen at?

elizabeth warren

1.2, unless the book gets boring, in which case, I’ve been known to go to 1.5. And occasionally, when I’m just like, oh, please, lord, let me get to the end, I’ve done a 1.8 and even a 2.0, but I’m not going to tell you which books those were. So I’m just about to finish up Mazie Hirono’s book, which is really terrific, “Heart of Fire.” And have you read “Pachinko” yet?

ezra klein

Oh, “Pachinko”‘s an amazing book.

elizabeth warren

Oh, I love it. Well, then if you liked “Pachinko,” have you read “Before the Coffee Gets Cold“?

ezra klein

I have not.

elizabeth warren

Read it. It’s by Kawaguchi and translated into English. And it translated very, very well, and it’s really terrific. And I’m rereading all of the Barry Eisler books. Have you ever read Barry Eisler?

ezra klein

No.

elizabeth warren

Oh, so he does these wonderful books. John Rain is an assassin. As Bruce and I, during the pandemic, we don’t fly, so we drive from Boston to Washington, Washington to Boston. And just so you know, I am a terrible rider. I get car sick, I get cranky. I get — I’m awful. I do not like eight-hour car trips. Now, Bruce helps all of that by speeding, so we get there faster. But the other way is, we’ve been listening to the John Rain books. Bruce had never read them. And it’s been a lot of fun. I love the series about people who are strong and principled and have a lot of tools at their disposal, including with assassins, tools I don’t have.

ezra klein

That sounds great. Senator Elizabeth Warren, it is always such a pleasure. Thank you.

elizabeth warren

Oh, and it’s good to talk to you, too, Ezra. Take care. [MUSIC PLAYING]

ezra klein

Thank you to Senator Elizabeth Warren for being here, to all of you for being here. If you enjoy the show, please give us a rating wherever you are listening to it, whatever your podcast app is, or send it to a friend. Before we go today, a couple recommendations, housekeeping things. One, we talked about student debt cancellation in this episode. And my colleagues over at “The Argument” had a really good debate on whether or not we should cancel student debt a few weeks back. So if you subscribe to “The Argument” wherever you get your podcasts, you can go hear that. It’s really worth the time. And then also, I’m teaming up with my fellow Opinion podcast hosts, Kara Swisher of “Sway” and Jane Coaston of the aforementioned “The Argument,” and columnist Farhad Manjoo for a free event for Times subscribers. We’re going to be debating the merits and dangers of cancel culture. And comedian Trevor Noah will be weighing in on the subject, too. That’s going to be Wednesday, May 12th. Times subscribers can RSVP at nytimes.com/cancelculture. “The Ezra Klein Show” is a production of New York Times Opinion. It is produced by Roge Karma and Jeff Geld; fact-checked by Michelle Harris; original music by Isaac Jones; and mixing by Jeff Geld.