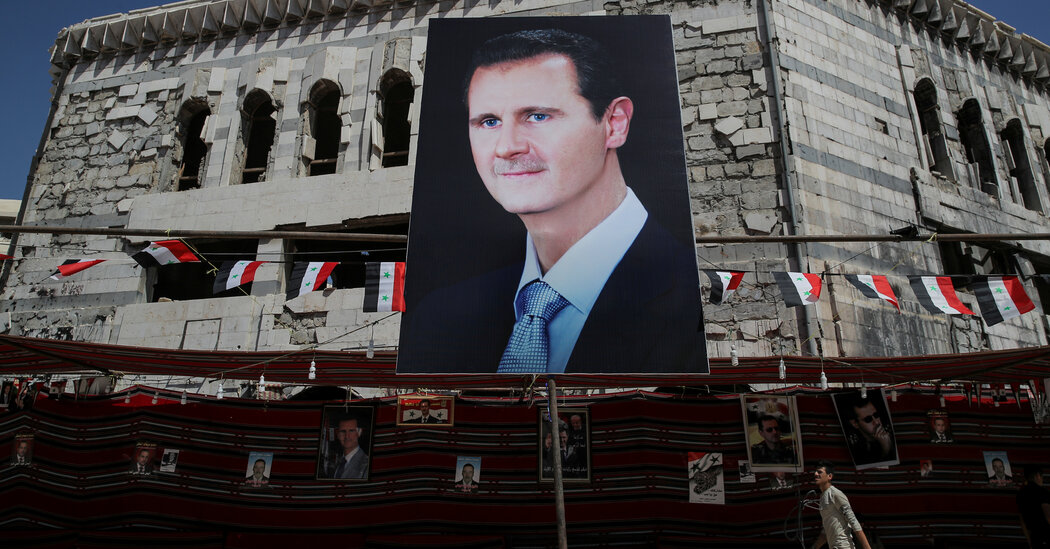

PARIS – Chemical ammunition experts have been compiling information for years that the Syrian government used these banned weapons against their own people, a war crime that has not yet been prosecuted and has been derisively dismissed by President Bashar al-Assad.

The first criminal investigations into Mr. al-Assad and his staff for the use of chemical weapons could now begin soon.

In an important step towards bringing Mr. al-Assad and his circle to justice for some of the worst atrocities in the decades-long Syrian conflict, judges from a special war crimes department in the French Palace of Justice have received a complaint about chemical weapons attacks in Syria, filed by three international human rights groups.

The complaint, which lawyers said judges would likely accept, calls for a criminal investigation into Mr. al-Assad, his brother Maher, and a litany of senior advisors and military officials who made up the chain of command.

Along with a similar complaint filed in Germany last October, the French complaint, filed on Monday and published on Tuesday, opens a new front designed to ensure that Mr. al-Assad and his hierarchy are fair in some way become.

Last but not least, the criminal investigations in France and Germany could seriously hamper the future of Mr al-Assad, who largely emerged victorious in the Syrian war, but with a pariah status that has blocked the international aid needed to rebuild his country.

Obtaining such aid could become even more difficult when Mr al-Assad and his leaders are accused in prosecuting war crimes in European courts, even if they consider such proceedings to be unlawful. Millions of Syrians who have fled to Europe and elsewhere as refugees are also unlikely to return home.

Steve Kostas, the chief attorney for the group that filed the complaints in France, said he focused on the August 2013 events in the city of Douma and the Eastern Ghouta region near Damascus – coordinated attacks, by whom the US government said they killed more than 1,400 people, making it the deadliest chemical weapon use in the world this century.

The victims of these attacks, who inhaled sarin nerve pathogens or chlorine fumes from bombs, are only a small fraction of the estimated 400,000 people who have been killed since the war in Syria began in March 2011.

More than 300 chemical weapons attacks in Syria have been documented by experts, including photos and videos of adults and children seized by convulsions, gasping and often choking.

Many of these pictures were published and shocked the world. So far, no one has had to answer for them.

“We want the French to conduct an independent investigation and ultimately issue arrest warrants for those responsible for these crimes against the civilian population,” said Kostas, a senior lawyer for the London-based Open Society Justice Initiative.

“We know that high-ranking offenders won’t be arrested anytime soon,” he said. But cases need to be built now to ensure law enforcement in the future.

The other two participating groups are the Syrian Archive, a documentation center in Berlin, and the Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression, based in Paris.

Among the witnesses they can bring with them are not only attack survivors, but also former members of the government who have been linked to the banned chemical weapons arsenal or are aware of how it works.

The filing comes amid speculation about moves by some countries to seek closer ties with Damascus, an informal recognition that Mr. al-Assad was not defeated. There was also talk of planning a reconstruction phase that would produce important treaties and facilitate the return of refugees.

But western countries, even those that have taken in significant numbers of refugees, firmly believe that impunity for the crimes is not an option for a future peace deal or normalization. So far, limited steps have been taken to hold elderly Syrians accountable.

Russia and China have blocked the route to the International Criminal Tribunal for Prosecuting Syrian Atrocities by using their veto in the United Nations Security Council, which could grant ICC jurisdiction.

“After 10 years and all these crimes there is no response from the international community, so the victims are trying to knock on all doors themselves,” said Mazen Darwish, an activist and former prisoner from Syria who founded the Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of expression.

“People die every day,” he said.

In the absence of an international court with jurisdiction over Syrian crimes, there has been a patchwork of accountability efforts for some time. Several countries, including Germany, Sweden and France, are persecuting or have already sentenced people found among the many Syrian refugees in Europe.

Most of them were low-ranking members of the Islamic State or the Syrian security forces who were accused of violating human rights.

However, for the first time, the complaint filed in Paris and a similar complaint by the same group in Germany targets the top tier of the Syrian government on the issue of chemical weapons – both for previous attacks and for what the complaints call secret program, the obviously violates international law.

The group’s complaint in Germany was submitted to the federal prosecutor’s office in Karlsruhe in October. It focuses on the sarin nerve agent attack in Eastern Ghouta in 2013 and the rebel-held village of Khan Sheikhoun in 2017.

Both France and Germany accept some form of universal jurisdiction that gives their national courts the power to prosecute those charged with heinous crimes.

Mr Kostas said France’s corporate responsibility law could also provide justification to provide evidence on companies that supplied Syria with chemicals and equipment for its banned chemical weapons arsenal.

The United Nations and the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons conducted investigations into Syria following the 2013 attack, but the evidence they accumulated has never led to accountability and has never identified the perpetrators by name.

The criminal investigation request is based in part on a two-year study of Syria’s chemical weapons program that goes beyond what other international investigations have undertaken, Kostas said. The study drew on a variety of sources including defectors, former insiders, employees, engineers, and people directly related to or related to knowledge of the program.

Gregory Koblentz, chemical and biological weapons expert and professor at George Mason University who reviewed the study, said that while there is a lot of open source material “it brings new information to light from defectors and insiders.”

Mr Koblentz called it “the most comprehensive and detailed report on the Syrian weapons program that is possibly available outside the secret services. It reveals new details in the chain of command and shows how big and complex this program was. And it can name it. “

The complaint filed in Paris also uses the Syria Archives, which contain more than three million videos sent by activists from Syria. It also relies on data from the Global Public Policy Institute, a research group in Berlin.

Tobias Schneider, a researcher at the institute, said he had verified 349 attacks in the past ten years, “significantly more than is generally known”. The Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, on the other hand, has only investigated 39 attacks as the organization identified them as limited resources.

Mr Dazen, who was imprisoned in Syria for three years and now lives in Paris, said the fight against chemical weapons was more than just an attack on his country.

“If they are not banished, no place is safe,” he said. “What’s next? They could be used on the Champs-Élysées.”