- The Red Road to DC started last week in the coastal state of Lummi north of Seattle and ends on July 29th in Washington, DC,

- The cross-country caravan will arrive on Saturday at Bears Ears National Monument in Utah, a particularly sacred place for Native Americans.

- The predominant imagery on the colorful totem that is being dragged across the country: an eagle diving to earth, a praying man and a salmon.

Two dozen Native American activists in 10 cars are hauling a totem pole across the country.

While this protest caravan may seem small, its message to Congress is oversized: give tribal peoples a say before granting access to land that tribal peoples consider sacred. The counter-argument: public land is there for everyone and the nation’s energy needs cannot be ignored.

Nowhere is this debate more heated than at the Bears Ears National Monument in southeastern Utah, a formidable archaeological and natural wonder that activists will accomplish on Saturday.

Former President Barack Obama reserved 1.35 million acres for the memorial at the end of 2016. Conservatives criticized the move as a government excess, and then-President Donald Trump reduced the size of Bears Ears by 85% in 2017. His fate is still at stake.

“Holy places and public lands are under sustained pressure from climate chaos and fossil fuel reliance, and we believe that under this administration we can change the role of federal government in that equation,” said Judith LeBlanc, director of the Native Organizers Alliance who spoke to USA TODAY as the caravan passed through Utah. “This is the political moment.”

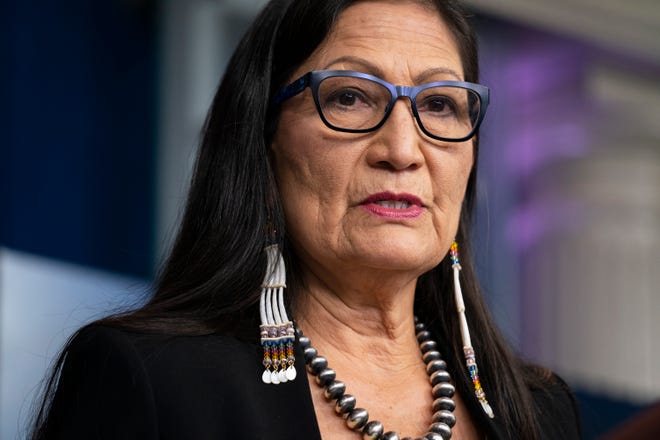

Local organizers were helped by the appointment of former US Congressman Deb Haaland of Laguna Pueblo, New Mexico to lead the Home Office and President Joe Biden’s restoration of the White House Native American Council.

Activists say the role of indigenous peoples in the recent elections should give them more say in policies that can help provide tribes with jobs, education and health care.

“Native Americans need to be at the decision-making table,” said LeBlanc, who belongs to the Caddo Nation of the southeastern states.

For most of the country’s nearly 600 nationally recognized tribes, land use and ownership are a top priority. While some tribes have succeeded on that front – last year the Supreme Court ruled that half of Oklahoma is on indigenous land, which had an impact on legal proceedings – most have spent the last few years protesting access to state , many of them in Indian countries granted by the Trump Administration to energy and mining companies.

From the Gila River to Bears Ears: Environmental activists renew their push to protect public land in the American Southwest amid changing politics

The result, say activists, is deep concern over land looting by fracking and oil pipelines, which are often of deep historical and religious significance to the indigenous people.

“Just as Notre Dame Cathedral is a symbolic structure for Catholicism, these landscapes are our cathedral,” said Pat Gonzales-Rogers, executive director of the Inter-Tribal Council of Bears Ears, based in Albuquerque, New Mexico. “We ask people to be in the same respectful mindset and show respect for this landscape as our people and tribal leaders do.”

Gonzales-Rogers added that while no sacred site is more important than another, Bears Ears, named after two towering ear-like buttes, is likely to test the power of the Presidency when it comes to oversight of the Antiquities Act of 1906, empowered by the President to “declare historical landmarks by public proclamation”.

Bears Ears supporters say Obama did this when he made it a memorial in one of his final gestures in office. Critics say the law was not designed to make such large areas of land available, potentially restricting access to a number of users.

“This bill should be used to prevent looting for the smallest negotiable area,” said Jeffrey McCoy, an attorney with the Pacific Legal Foundation, a libertarian public-interest law firm that represented ranchers who said Obama’s statement denied them access Land took a long time. This case has been put on hold as Biden is reviewing his predecessor’s action.

McCoy said it is not up to the presidents of either party to decide the fate of massive state holdings, but “that is the job of Congress and the National Park Declaration.”

Bears Ears chairman Gonzales-Rogers said activists are pushing lawmakers to increase the size of the national monument over what Obama has granted to nearly 2 million acres.

Realizing that the fate of the Indian country has long been tied to federal politics, various indigenous groups came up with the idea of driving from Washington State to Washington, DC, and stopping at some of the most controversial indigenous holy sites.

The journey, called Red Road to DC: A Tote Pole Journey for the Protection of Sacred Places – a name that refers to a journey from addiction to sobriety – started last week in the coastal nation of Lummi north of Seattle and ends with events on the nation’s capital on July 29th.

Stops along the meandering trail include Chaco Canyon in New Mexico (July 18), where fracking is underway in an area where thousands lived between AD 850 and AD 1200; Standing Rock, North Dakota (July 24), the site of years of protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline; and Mackinaw City, Michigan, where tribes are fighting to close a pipeline over fear a spill could contaminate lake water.

Dig deeper into race and identity: Subscribe to This Is America, USA TODAY newsletter

The idea of taking the trip along with a massive carved totem pole was in line with best protest tradition: having something that makes those who see it ask questions, LeBlanc said.

“It’s about raising people’s awareness of what is happening to our nation’s land,” she said.

Totem poles are a traditional feature of the Indian tribes from the Pacific Northwest and are considered sacred symbols. This particular totem was made by Lummi artisans called House of Tears Carvers over three months. It is 25 feet high, 43 inches wide, and was carved from 400 year old red cedar.

The predominant imagery of the colorful totem includes an eagle plunging to earth, a praying man, and a salmon. There is also a woman with a girl nearby, a tribute to the way grandmothers often teach the Aboriginal customs and language to the younger generation. Also carved into the totem are seven tears that, according to the organizers of Red Road to DC, represent seven generations of Native Americans who have suffered at the hands of non-natives.

As the caravan continues, activists hope to use the totem and their gatherings to draw attention to the universal need to protect nature at a time when climate crises – from fires in the west to storms in the east – are a growing threat.

Native Americans, they argue, are uniquely willing to be stewards of land that once belonged to them alone.

“Since the beginning of time, our peoples have gone to sacred places to collect medicines, connect with our ancestors, pray, and lift their spirits,” said LeBlanc. “We know how best to preserve and protect these places to ensure that these places continue to be there for our people and all people.”