SAN FRANCISCO – President Biden and many Washington lawmakers are currently concerned about computer chips and China’s ambitions with basic technology.

But a huge machine that was sold by a Dutch company has turned out to be an important lever for politics – and shows how unrealistic a country’s hopes for building a completely self-sufficient supply chain in semiconductor technology are.

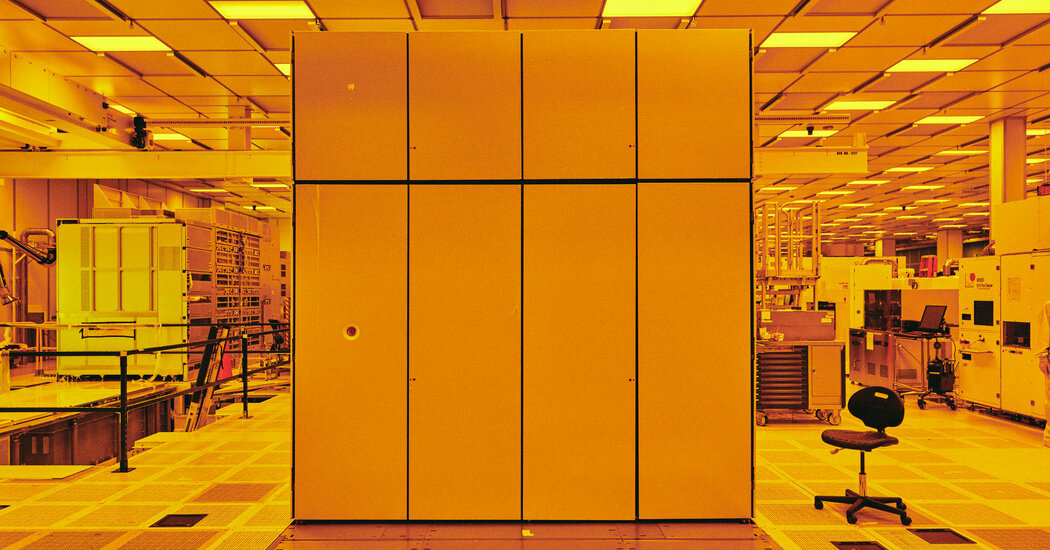

The machine is manufactured by ASML Holding based in Veldhoven. His system uses a different type of light to define ultra-small circuits on chips and pack more power into the tiny silicon wafers. The tool, which took decades to develop and launched for high volume production in 2017, costs more than $ 150 million. 40 containers, 20 trucks and three Boeing 747s are required for shipping to customers.

The complex machine is widely recognized as necessary for the manufacture of the most advanced chips, a skill with geopolitical implications. The Trump administration has successfully used the Dutch government to block the delivery of such a machine to China in 2019, and the Biden administration has shown no sign of reversing that stance.

Manufacturers can’t produce high-end chips without the system, and “it’s only made by the Dutch company ASML,” said Will Hunt, a research analyst at Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology, who concluded it would take time China would take at least a decade to build its own similar equipment. “From a Chinese point of view, that’s frustrating.”

ASML’s machine has effectively become a bottleneck in the supply chain for chips that act as the brains of computers and other digital devices. The development and production of the tool on three continents – using know-how and parts from Japan, the United States and Germany – is also a reminder of how global this supply chain is and provides a reality check for every country that has a semiconductors I want to make a leap forward myself.

This includes not only China, but also the United States, where Congress is discussing plans to spend more than $ 50 billion to reduce reliance on foreign chipmakers. Many branches of the federal government, particularly the Pentagon, are concerned about the US’s dependence on Taiwan’s leading chip maker and the island’s proximity to China.

A study conducted earlier this spring by the Boston Consulting Group and the Semiconductor Industry Association estimated that creating a self-sufficient chip supply chain would cost at least $ 1 trillion and soar the prices of chips and products made with them.

This goal is “totally unrealistic,” said Willy Shih, a management professor at Harvard Business School who studies supply chains. ASML’s technology “is a great example of why there is global trade”.

The situation underscores the critical role played by ASML, a once unknown company whose market value now exceeds $ 285 billion. It’s “the most important company you’ve never heard of,” said CJ Muse, an analyst at Evercore ISI.

Founded in 1984 by electronics giant Philips and another tool maker, Advanced Semiconductor Materials International, ASML became an independent company and by far the largest supplier of Chip manufacturing equipment that includes a process called lithography.

Using lithography, manufacturers repeatedly project patterns of chip circuits onto silicon wafers. The more tiny transistors and other components that can be added to a single chip, the more powerful it becomes and the more data it can store. The pace of this miniaturization is known as Moore’s Law, named after Gordon Moore, a co-founder of chip giant Intel.

In 1997, ASML began investigating a switch to use extreme ultraviolet or EUV light. Such light has ultra-small wavelengths that can create much smaller circuits than is possible with conventional lithography. The company later decided to make machines based on this technology, an expense that has cost $ 8 billion since the late 1990s.

The development process quickly became global. ASML is now assembling the advanced machines with mirrors from Germany and hardware developed in San Diego that generates light by blasting tin droplets with a laser. Important chemicals and components come from Japan.

Peter Wennink, CEO of ASML, said that a lack of money in the company’s early years led to the integration of specialty vendor inventions and the creation of what is known as a “collaborative knowledge network” that innovates quickly.

“We were forced not to do what others can do better,” he said.

ASML built on other international collaborations. In the early 1980s, researchers in the United States, Japan, and Europe began thinking about radical changes in light sources. The concept was picked up by a consortium that included Intel and two other US chip manufacturers as well as the laboratories of the Department of Energy.

ASML joined in 1999 after more than a year of negotiations, said Martin van den Brink, President and Chief Technology Officer of ASML. The company’s other partners were the Imec research center in Belgium and another US consortium, Sematech. ASML later attracted large investments from Intel, Samsung Electronics, and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company to fund the development.

This development was made difficult by the characteristics of extreme ultraviolet light. Lithography machines typically focus light through lenses to project circuit patterns onto wafers. But the small EUV wavelengths are absorbed by glass, so lenses don’t work. Mirrors, another common tool for directing light, have the same problem. This meant that the new lithography required mirrors with complex coatings that together better reflect the small wavelengths.

So ASML turned to the Zeiss Group, a 175-year-old German optics company and long-term partner. His contributions included a two-ton projection system for extreme ultraviolet light with six specially shaped mirrors that are ground, polished and coated over several months in a complex robot process that uses ion beams to remove defects.

The generation of enough light for the rapid projection of images has also led to delays, said van den Brink. But Cymer, a San Diego company that bought ASML in 2013, finally improved on a system that directs pulses from a high-powered laser to tin droplets 50,000 times per second – once to flatten them and a second time to vaporize them – to create intense light.

The new system also required redesigned components called photomasks, which act like stencils on projected circuit designs, and new chemicals applied to wafers that create these images when exposed to light. Japanese companies supply most of these products today.

Since ASML launched its commercial EUV model in 2017, customers have bought about 100 of them. Buyers include Samsung and TSMC, the largest service-producing chips from other companies. TSMC uses the tool to make the Apple-designed processors for its latest iPhones. Intel and IBM have stated that EUV is critical to their plans.

“It’s definitely the most complicated machine people have built,” said Darío Gil, senior vice president at IBM.

The Dutch restrictions on exporting such machines to China in force since 2019 have not had a major financial impact on ASML as it has a backlog of orders from other countries. But around 15 percent of the company’s sales come from the sale of older systems in China.

In a final report to Congress and Mr Biden in March, the National Artificial Intelligence Security Commission suggested extending export controls to some other advanced ASML machines too. The Congress-funded group seeks to limit the advances in artificial intelligence with military applications.

Mr. Hunt and other policy experts argued that blocking additional sales would hurt ASML without much strategic benefit, given that China was already using these machines. So does the company.

“I hope common sense will prevail,” said van den Brink.