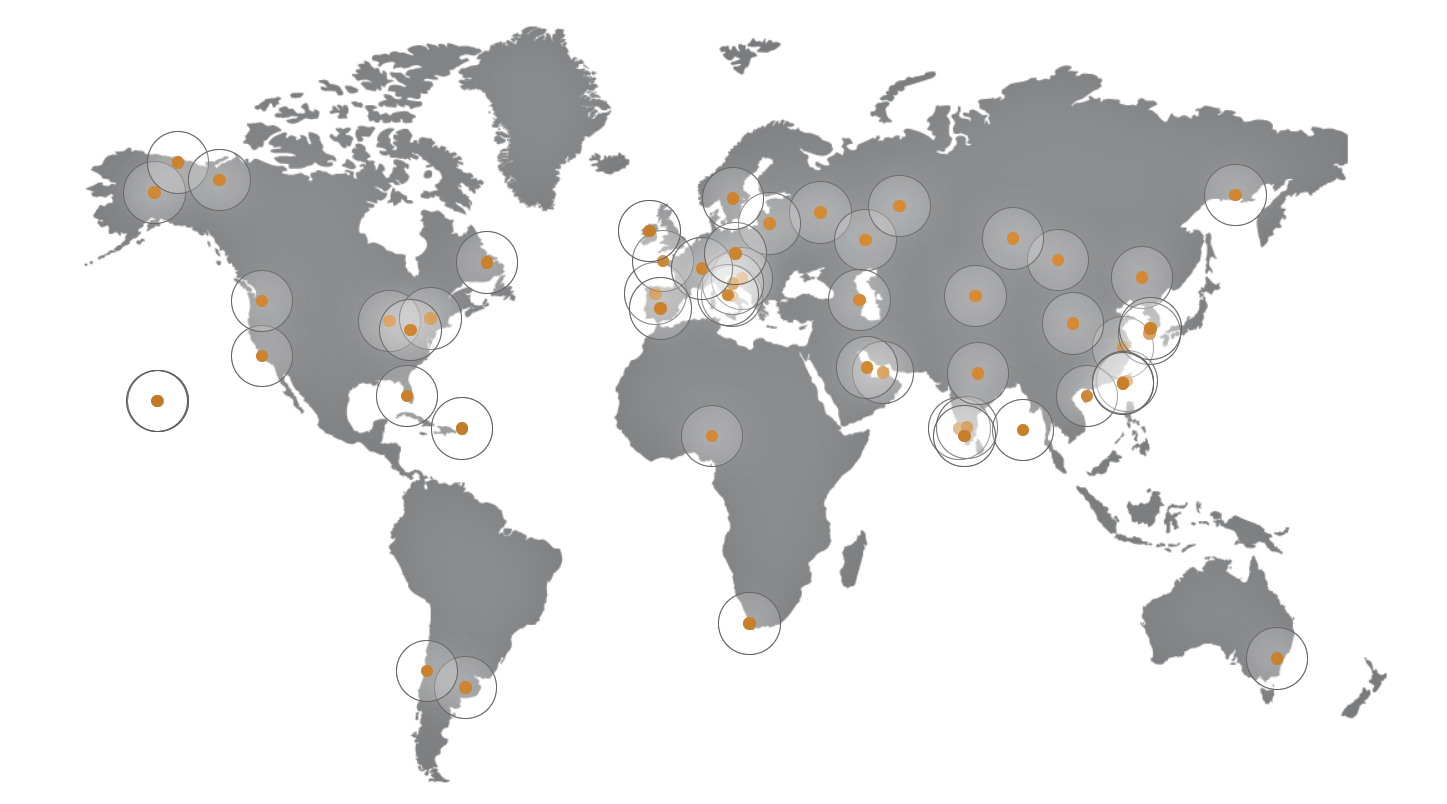

RBC Signals uses satellite ground stations around the world. (Graphic of the RBC signals)

The warnings about the possible dangers of foreign alliances go back to George Washington’s farewell speech – but in the space age the problems related to international relations are much more nuanced.

At least, that’s the view of Christopher Richins, the founder and CEO of RBC Signals in Redmond, Washington.

RBC Signals acts as a broker for global satellite connectivity services and has the US government among its customers. Since RBC’s business model is based on partnerships with satellite ground stations around the world, RBC must work with countries that the US government sees as rivals on the space border – particularly Russia and China.

“You don’t have to have the US government as a customer,” Richins told GeekWire. “However, if at some point you intend to consider things like cybersecurity and management structure, knowing your customers and your investors, then with all of these things you can remove some of the potential barriers to market entry to take advantage of these opportunities. ”

The problems encountered by Momentus Space, one of RBC Signals’ clients, serve as a cautionary story. The proposed merger of the space tug startup with a blank check company, Stable Road Acquisition Corp., has been delayed amid concerns by the US government about the Russian co-founders of Momentus. Additionally, Momentus’ first launch plans have been rejected by the Federal Aviation Administration for similar reasons.

Foreign entanglements can also endanger established companies like Virgin Galactic: A few years ago, the space company founded by British billionaire Richard Branson had to obtain a license exemption from the State Department to fly non-US citizens with its SpaceShipTwo spaceplane. Even after this exemption was granted, a controversy arose over the sale of tickets to Chinese citizens.

In light of such concerns, Richins said that RBC Signals has acted cautiously in its six years of existence.

The origins of RBC Signals reflect the complexity involved in creating a space startup with international reach. The company started in 2015 with Russian-born Olga Gershenzon, who served as the co-founder and chief strategy officer of Richins.

Gershenzon and her husband Vladimir also founded a Russian company called Scanex, which processes satellite data and distributes images of the earth. Scanex has business relationships with companies such as Airbus and the US Geological Survey. However, in 2018, some of the company’s investors were named in news of Russian-influenced operations targeting the National Rifle Association.

Olga Gershenzon’s LinkedIn page states that she left RBC Signals in 2017 and that the couple sold almost all of its shares in Scanex before forming RBC. “Olga has not been associated with RBC in several years and I am not aware of any association with any of these NRA things,” said Richins. “This is actually the first time I’ve heard anything between Scanex and that.”

Richins said RBC is making great efforts to avoid foreign entanglements.

“RBC Signals is a multinational company,” he said, “but we are structured so that we can have US operations that are basically just US personnel, and then we have a separate part of the company that. ” is global in nature. “

Cyber security is a particular concern.

“All of our customer data is protected according to industry cybersecurity standards, and our customers choose where to store their data,” said Richins. “They want to be selective about where their information ends up, and because of the global nature of our network, we can take that into account.”

Foreign investment is another topic that requires special attention. Previous investors in RBC Signals included China’s Baidu Ventures, Mexico’s MxSpace, and venture capitalists from Singapore and the Middle East. More recently, RBC Signals reported a $ 1.2 million financing round with some investments from non-US donors.

Richins said such transactions must be structured to meet the requirements of the United States Foreign Investment Committee or CFIUS.

“We have converted debt into equity, paying particular attention to terms that keep us within the CFIUS Safe Harbor requirements,” said Richins in an email. “CFIUS has concerns ranging from ownership to information rights, and so on. We weren’t a problem before the last investment and we are not a problem after the last investment, but issues like this need to be considered when structuring such an investment. “

Looking ahead, Richins noted that a few years ago the U.S. government helped commercial space companies become more competitive in international markets by relaxing trade restrictions.

“I think there will be further refinement of policy to protect US national security and interest while preserving our ability to lead the global space economy,” he said. “I think that’s a pendulum swing.”

Richins just hopes the pendulum doesn’t swing back too far.

“I hope we will continue to lead,” he said, “and that our regulatory policies will continue to support a good and healthy market for US services overseas.”